I was thirteen when I first picked up Lolita. Or rather, when I first carried it around like a literary accessory, dog-eared, underlined in all the wrong places, proof that I was different. Though I did not fully understand it, I wanted to. It was the kind you read cross-legged in a school corridor, thinking it made you complicated, tragic, poetic.

But when I revisited it at university, I realised something: Lolita wasn’t just misunderstood. It had been rewritten. And not by Nabokov, but by pop culture, fashion, and the people who turned Dolores Haze into an aesthetic rather than what she was: a victim.

The Lolita aesthetic, marked by polka-dot dresses, gingham, knee socks, red lips, and heart-shaped sunglasses, has endured as one of fashion’s most quietly unsettling trends. It is the kind of hyper-feminine, youthful styling that flirts between sweet and suggestive. It is not just about the clothes. It is about what they imply.

Every major Lolita adaptation, from Kubrick’s 1962 version to Lyne’s 1997 film, has shaped how we remember her. Sue Lyon, in the infamous garden scene, where Humbert first lays eyes on her, lounges in a cherry-red bikini, sunglasses perched on her nose, more Hollywood starlet than a child. Dominique Swain, with white ribbons in her hair and a sheer dress clinging to her body, drenched from the garden hose, is framed as something delicate yet provocative.

Image: Lolita garden scene via JammerSmith Wordpress.

Neither adaptation gave us Nabokov’s Lolita, the unkempt, scrappy child, all skinned knees and chewed-up pencils. Instead, they turned her into something else. A girl suspended between innocence and seduction. The ultimate male-gaze creation.

And fashion followed.

The Lolita aesthetic, or, as Tumblr called it in the early 2000s, nymphet fashion, became a style guide. Pinterest boards and TikTok trend cycles have kept it alive, rebranding it under softer, more palatable names: ‘coquette’, ‘soft girl’, ‘angel-core’. It is still the same formula, short skirts, delicate bows, the aestheticised innocence of a girl not quite a woman, but sexualised anyway.

Fashion has never been shy about playing with the idea of innocence undone. We have seen it with Brigitte Bardot in baby-doll dresses, with Lana Del Rey’s ‘Born to Die’ era styling, with every run of the Miu Miu micro-mini skirt. And while there’s nothing inherently wrong with femininity, there is something deeply uncomfortable about the continued repackaging of an aesthetic rooted in the romanticisation of a child.

Image: Model Alice Dodd at Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show, 1996 by Evan Agostini via Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Image: Lana Del Rey photoshoot (April 19-20, 2009) by Edward Smith, published in Blurt Magazine Issue #1, Fall 2009.

Image: Miu Miu Spring 2002 runway show at Milan Fashion Week via Pinterest.

When the Fashion Industry Crossed a Line

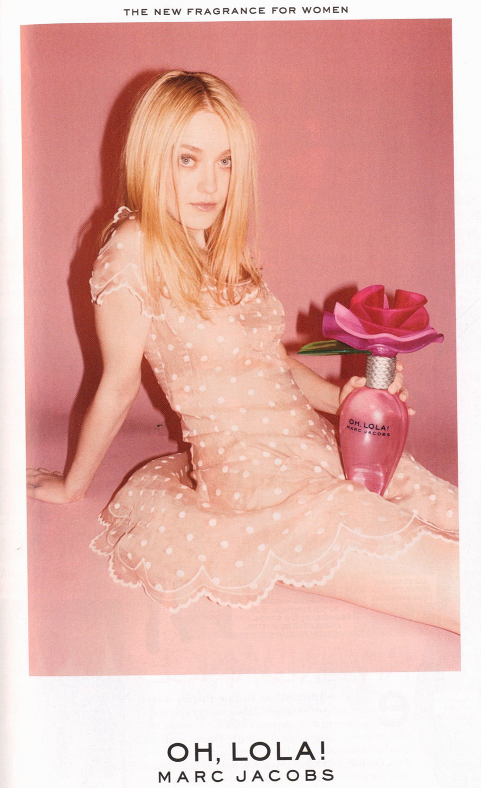

Few ad campaigns capture this better than Marc Jacobs' ‘Oh, Lola!’ perfume in 2011. The perfume itself, a fuchsia bottle topped with a giant blooming flower, was already a call back to hyper-femininity. But the controversy came with its campaign: a 17-year-old Dakota Fanning, sitting in a sheer polka-dot dress, a perfume bottle deliberately positioned between her legs.

Image: Dakota Fanning for Coty's Oh Lola! perfume campaign, via Campaign Live.

The polka dots? A clear nod to Lolita’s most iconic costume design. The pose? Suggestive enough for the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) to ban the advert, stating it "sexualised a child."

But was it an isolated case?

Hardly.

The Lolita aesthetic has seeped into high fashion and beauty advertising for decades. Think of the baby-faced models styled to look younger, the editorials that frame female sexuality as something childlike, and prettily naive. The question isn’t why brands keep doing this. It’s why we keep letting them?

Why the "Lolita Aesthetic" Won’t Die

Because fashion sells fantasy. One of the most persistent, profitable fantasies is a woman who is desirable but does not know it.

It is the same reason why beauty brands market "youthful glow" like it is the holy grail. Why do trends like ‘coquette’ and ‘soft girl’ keep cycling back, just rebranded with prettier words? Fashion has spent decades blurring the line between innocence and sexuality because that tension sells.

But we should know better by now.

To Conclude

Revisiting Lolita as an adult made me realise that what I once found alluring was never meant to be. Dolores never had control of her narrative. Humbert did. And yet, decades later, we are still dressing up in a version of her that never existed in the first place.

Fashion, at its best, reinvents. But some things are not meant to be revived. It is time to let Lolita go, not as a novel, but as a trend. It is time to stop packaging her into something aspirational and to stop mistaking exploitation for aesthetics.

If there is one thing more troubling than the persistence of the Lolita aesthetic, it is how effortlessly we keep buying into it. Over and over again, just in different fonts.

Great article!

such an interesting read!